This might be the favorite book of my summer reading season. There's still another month or so of heavy reading ahead of me, but Colum McCann's book is going to be hard to beat. It's more than a novel, it's a multifaceted, multi-voiced tale of New York City during August 1974, where each voice

relates to the others or a certain remarkable event. I can't reveal many details without taking away the astonishment aspect of this story. The wonderment is less in the content than in the magnificent telling. Evidently, the National Book Award judges felt the same way since this book won that award in 2009. It also won the 2011 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award which is also a huge honor.

I met Colum McCann in June, at a writers' conference where he spoke about his writing and research process. I sat enraptured as he spoke of living among the subterranean homeless people who live in New York City subway tunnels. This research was for another book, but when reading Let the Great World Spin, I could imagine him researching its characters as thoroughly. How else could he write convincingly in the voice of a prostitute or a radical priest?

After his talk, as he signed my book, I awkwardly attempted to chat him up, He was polite, but my questions were dumb. I was starstruck. He explained that he wrote something in Irish (we'd say Gaelic) that means...um...oh my gosh, I was so starstruck I forgot. I probably wrote the translation down somewhere. Here is a photo of that treasured autograph:

Colum McCann is from Ireland technically, although he has demonstrated that he is a citizen of the world. One of his central characters in this novel is an Irish guy who comes to the United States to visit his brother. (For this tiny bit only McCann could write from his own experience rather than his virtuosic research.) The brother is a father (a priest) who works in a nursing home but looks after a colony of prostitutes working near his home in the Bronx. That alone would be enough of a story for a typical novel, but McCann adds more fully-realized characters and stories, relates them all to each other and the spectacle of a tightrope walker who walked a wire strung between the two World Trade Center towers in 1974.

Here's something unique: McCann collaborated with musician Joe Hurley to create a song cycle based on the book. "The House that Horse Built (Let the Great World Spin)" is the result. I just now learned of it, and that Patti Smith sings on it. YES I'm going to score a copy!

You still have some summer left. There will be stormy days and super-hot days. My recommendation is to make yourself comfortable with a glass of ice-water, possibly infused with strawberries, and read this book.

Thursday, August 1, 2019

Monday, July 1, 2019

A NATURALIST AT LARGE by Bernd Heinrich

Do Phoebes benefit from making their nests near humans so that humans will chase away predators? I don't know, but naturalist Bernd Heinrich thinks that might be the case. He writes about phoebes in his essay, "Phoebe Diary," and provides another example from nature: "some tropical bird species rear their young near wasp nests and depend on the insects to repel predators." So, replace tropical birds with phoebes and wasps with humans, and the idea seems plausible.

Heinrich has been writing about nature (birds, insects, trees, flowers) for decades, but I've only been reading him for the past few. This collection of essays is a treasure trove of interesting nature writing accessible to people like me who never bothered to get a Biology degree or learn to identify birds outside their own state.

Did you know the top, vertical branch of a conifer is its leader? It contains special hormones called gibberellins which promote its upward growth while inhibiting the growth of nearby buds and twigs. Lower branches still grow outward, though, which produces the conical shape which helps it grab essential light in a forest. If you haven't guessed, we're talking about basic Christmas trees here.

Two of Heinrich's special interests in nature are ravens and irises. He's written on both extensively. The book, Mind of a Raven, was a top-seller, not solely in nature books. It's on my TBR (To-Be-Read) list with a star next to it. As for irises, Heinrich spent so much time observing these flowers that he noticed the buds always unfurl in a counterclockwise direction. This observation led him to discover that most buds do unfurl this way, too. He wonders how they know to do that, and I wonder how that question ever occurred to him.

I sincerely endorse this compelling book of nature essays for anyone who wants to learn more about birds, bees, flowers, trees, and basically our planet. Yellow birch trees grow on rock. Kinglets huddle. Bees regulate their hive temperature. Carnivorous lady fireflies eat male fireflies of other species when responding to their mating calls. Really, this stuff is fascinating and you should read it. In a hammock. Or a treehouse. Or a park bench.

Heinrich has been writing about nature (birds, insects, trees, flowers) for decades, but I've only been reading him for the past few. This collection of essays is a treasure trove of interesting nature writing accessible to people like me who never bothered to get a Biology degree or learn to identify birds outside their own state.

Did you know the top, vertical branch of a conifer is its leader? It contains special hormones called gibberellins which promote its upward growth while inhibiting the growth of nearby buds and twigs. Lower branches still grow outward, though, which produces the conical shape which helps it grab essential light in a forest. If you haven't guessed, we're talking about basic Christmas trees here.

Two of Heinrich's special interests in nature are ravens and irises. He's written on both extensively. The book, Mind of a Raven, was a top-seller, not solely in nature books. It's on my TBR (To-Be-Read) list with a star next to it. As for irises, Heinrich spent so much time observing these flowers that he noticed the buds always unfurl in a counterclockwise direction. This observation led him to discover that most buds do unfurl this way, too. He wonders how they know to do that, and I wonder how that question ever occurred to him.

I sincerely endorse this compelling book of nature essays for anyone who wants to learn more about birds, bees, flowers, trees, and basically our planet. Yellow birch trees grow on rock. Kinglets huddle. Bees regulate their hive temperature. Carnivorous lady fireflies eat male fireflies of other species when responding to their mating calls. Really, this stuff is fascinating and you should read it. In a hammock. Or a treehouse. Or a park bench.

Labels:

bees,

Bernd Heinrich,

birds,

fireflies,

irises,

kinglets,

Naturalist,

nature,

phoebes,

trees

Friday, May 17, 2019

RUN, RIVER by Joan Didion

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live...We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the "ideas" with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.”

Joan Didion, "The White Album" from The White Album

Run, River (1963) is a novel by one of my favorite essayists, the writer's writer Joan Didion. I never met a Didion essay I didn't like, a lot. She writes about suburban shopping malls, the opulent mansions in Newport, lots about California including the Manson family, and all sorts of social commentary. She wrote a couple of memoirs after losing her daughter and her husband within a couple years of each other. I'd never read one of her novels until this month, when I downloaded Run, River and listened to it in the car. I didn't know if my fascination with her writing would carry over to her novels. It took me some time to get into it, but by the halfway point I was engrossed. The character development and nuances of storytelling are masterful. I don't know how Didion did it, but I started thinking I was (protagonist) Lily, while alone with her in the car. We have little in common, so it wasn't that I related to her thoughts, feelings, and bad decisions. I just understood her thanks to Didion's fantastic writing.

Lily, Everett, Martha, Joe, Ryder, and a few parents and offspring populate the novel. I'm not going to give awayany secrets, because the way Didion reveals those secrets is part of the beauty of the novel. At least one of those characters end up dead, and please don't expect this author to tell you straight out how this happens. Nope, she casually mentions that person's funeral merely as a point on a timeline when she's describing another event. Wait, what? Did I miss something? If I had been reading a print book, I could have paged back a bit to see what I accidentally skimmed over. With an audio book, there's not a possibility to go back especially when driving. It would have been a waste of time anyway, because this was simply a cavalier mention of a death that hasn't happened yet. Eventually, Didion gets around to telling us what happened to this character in the most deliciously suspenseful way. There are plenty more storytelling treasures here.

That quote at the top of this post is a favorite of many Joan Didion fans. It comes at the beginning of her autobiographical essay, "The White Album" from a collection by the same name. The essays were written between 1968 and 1978. "The White Album" is the essay in which she writes about Charles Manson, meeting Jim Morrison and the Doors, and other tales of 1960s California. She demonstrates her unique gift for people-watching in these essays, and guess what: she "watches" her fictional characters as astutely. Through her descriptions of Lily, Everett, and Martha, along with insight into what they are thinking and how they are reacting, the story crescendos to that death I told you about (vaguely). "We tell ourselves stories in order to live..." and to understand how others live. The people of Run, River make mistakes and bad decisions and live their lives, and Joan Didion helps us understand them. Sometimes we read stories in order to understand life, don't you think?

Labels:

audio books,

Joan Didion,

Run River,

The White Album

Friday, March 8, 2019

Zora Neale Hurston, Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo"

Zora Neale Hurston, Barracoon:

The Story of the Last “Black Cargo.” (Amistad, 2018).

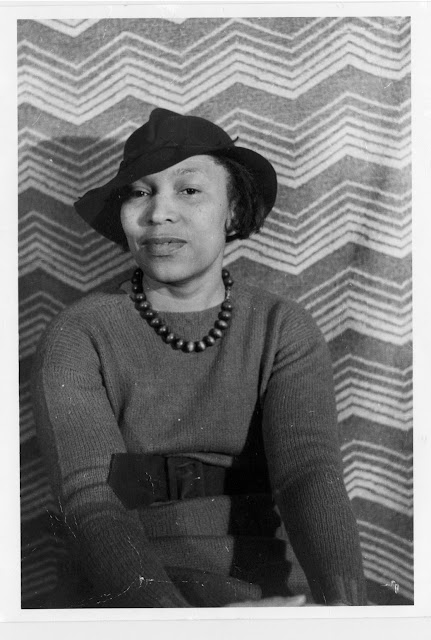

Zora Neale Hurston is known for her award-winning fiction

and poetry, but her latest book is a precious gem of nonfiction. She was one of the stand-out writers of the Harlem Renaissance, and she informed her stories and poems with astute observations of the people and cultures about which she

wrote. She frequently set her stories in northern Florida where she grew up and transcribed her characters' speech to represent how they actually spoke. (This was innovative then, but we see it often now.) A trained

cultural anthropologist, Hurston traveled in 1927 to Plateau, Alabama, near where she was born, to

interview Cudjo Lewis.

Cudjo Lewis was the last survivor of the illegal slave trade. He arrived in Alabama aboard the Clotilda in 1860. Hurston tells two stories about Lewis in this important

book. First, there’s Cudjo Lewis as an old man of 86, not sure he should trust

Hurston, and not always forthcoming about his history. She visits him

frequently, observing his daily routine, and her persistence pays off. He becomes somewhat comfortable with her, at least most days. The second thread winding through this book is Lewis’s personal tale of the slave traders violently capturing him (then known as Kossola) and some other people from his village and then the Middle Passage, their journey to the United States. His ship, the Clotilda, was the last slave

ship out of Africa to cross the Atlantic Ocean. He and his countrymen were considered

“cargo” and he remembers the awful experience clearly. Both stories, 1927 Cudjo and 1860 Kossola, are

illuminating, gripping, and long overdue, appearing 91 years after Hurston’s

interviews.

|

| Zora Neale Hurston, Photographed by Carl Van Vechten, around the time she was working on Barracoon |

Friday, February 1, 2019

THE LIBRARY BOOK by Susan Orlean

I read this book with my ears. I wished for photos and illustrations, but I just can't own every book I read. But I wanted this one. I really wanted this one, considering my 25-year history working in libraries and a lifetime of loving libraries and simply the idea of libraries. I read it with my ears, meaning I listened to the author read it as I drove around in my car. Susan Orlean is one of my top-shelf favorite Creative Nonfiction authors of all time, so it was a treat to hear her interpret her work just for me. Then my friend, Sue, a different Susan, told me that she got me a book for Christmas and she hoped I hadn't read it...and I pulled the red-covered book out of the wrapping... and gleefully shrieked, "I DID read it, BUT I really wanted to HAVE it!" I was so happy. After listening to Susan O.'s descriptions of the L.A. Public Library, and the person of interest who may have set it on fire, and other interesting personalities in the history of libraries, I now have photos of them and the correct spellings of their names, and I can re-read sections any time I want. I am so happy. YAY!

The Library Book, (Simon & Schuster, 2018), is the story of the big L.A. Library fire of 1986 told in-depth with information about events leading up to, stuff happening simultaneously, and things that happened after. That story alone is compelling, but I mentioned Susan Orlean writes Creative Nonfiction. She goes in and out of library history, and then back to the L.A. story, and never loses the reader's interest. I don't know if you are aware of this, but you can check with my friends who have heard my stories: libraries are not boring. Susan Orlean, lover of libraries, has done her research and interviewed people, and come up with fascinating stories to weave into the tale of the 1986 California fire.

Orlean pays homage to the institution of libraries, and the idea of libraries, and the movers and shakers of the library world, past and present. The Library Book got a lot of positive buzz in late 2018 when it was released and made it onto many end-of-the-year best-of lists. In this digital age, when I still get questions from the unenlightened about the future of libraries and librarians, this is sweet validation. (We'll always need human brains to organize information, retrieve it efficiently, and teach other humans how to retrieve it.) This is a treasure of a book and should be required reading (or listening) for everyone, enlightened or not.

The Library Book, (Simon & Schuster, 2018), is the story of the big L.A. Library fire of 1986 told in-depth with information about events leading up to, stuff happening simultaneously, and things that happened after. That story alone is compelling, but I mentioned Susan Orlean writes Creative Nonfiction. She goes in and out of library history, and then back to the L.A. story, and never loses the reader's interest. I don't know if you are aware of this, but you can check with my friends who have heard my stories: libraries are not boring. Susan Orlean, lover of libraries, has done her research and interviewed people, and come up with fascinating stories to weave into the tale of the 1986 California fire.

Orlean pays homage to the institution of libraries, and the idea of libraries, and the movers and shakers of the library world, past and present. The Library Book got a lot of positive buzz in late 2018 when it was released and made it onto many end-of-the-year best-of lists. In this digital age, when I still get questions from the unenlightened about the future of libraries and librarians, this is sweet validation. (We'll always need human brains to organize information, retrieve it efficiently, and teach other humans how to retrieve it.) This is a treasure of a book and should be required reading (or listening) for everyone, enlightened or not.

|

| A librarian reading The Library Book in a library |

Labels:

California,

Creative Nonfiction,

fire,

L.A.,

libraries,

library,

Los Angeles,

public libraries,

red book,

reference librarian,

Susan Orlean

Tuesday, January 1, 2019

REALITY HUNGER: A MANIFESTO, by David Shields

Reality Hunger is a thought-provoking book. Nonfiction writers like me will probably come away from it thinking about where to draw the line between fiction and nonfiction. Should there be a line at all? Maybe a blurrier line? Do we need new forms or a new taxonomy? Are we obsessed with reality? (I think I am.) Non-writers will probably ponder how the books they read are put together. Did the author base this novel on facts, possibly autobiographical? Is this alleged nonfiction piece journalistically nonfiction? Consider the books you read, but the magazine articles, too, and the television you watch. (Reality TV!) True? Not true? Have you investigated? Are you skeptical?

Reality Hunger is made up of short, numbered entries that circle around a particular cryptically-named topic: Memory, Books for people who find television too slow, Contradiction, Thinking, Manifesto. Don't get too hung-up on the section titles, though, because the numbered entries are all interesting, even if the section titles are not inviting. Check this one out:

615 What actually happened is only raw material; what the writer makes of what happened is all that matters.

This rings true for me, the creative nonfiction writer, because I take an experience, a thought, a place, or even the concert I'm watching on PBS right now, and create some analysis of it. It is a fact that I am watching the Vienna Philharmonic New Year's concert right now on my TV. You can't argue with that. To make this story my own, I have to provide some sort of analysis or reaction. You may disagree with me that this concert is an annual treat, but you can't disagree with me that I see it as an annual treat. Tonight's host, Hugh Bonneville (from Downton Abbey) was just standing in the Vienna Opera House!!! You may not be excited by Hugh Bonneville or the Vienna Opera, but I am because I am a Downton fan and I got to tour the Vienna Opera when I was there in 2015. I remember its opulence, and I remember being impressed at how important opera is to Viennese culture. While you may not agree with me or share my taste or travel history, but reading my thoughts, you understand why I enjoy watching this concert on TV. Maybe I haven't convinced you to watch it, but I have explained my music nerd-ness. Go back to #615 above and read it again.

573 To write only according to the rules laid down by masterpieces signifies that one is not a master but a pupil.

Think about Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms (staying in Austria) for example: if they hadn't broken the musical rules they were taught we probably wouldn't remember them today. They broke the rules and created new art that got attention. They were innovators! I chose this excerpt because it illustrates the concept in this book that got the biggest reaction out of me. At the end of the book is an Appendix. Here, the author, David Shields, explains that the numbered quotes were not all his original thought. Some are. Some, like #573 above, are not. Personally, I did not appreciate not knowing as I read the book that these were not all David Shields's thoughts. In fact, in the Appendix he writes, "However, Random House lawyers determined that it was necessary for me to provide a complete list of citations; the list follows (except of course for any sources I couldn't find or forgot along the way.)" He encourages the reader to tear these pages out and destroy them. WHAT?!?!?!?! I spend my life teaching college students how to cite their sources and why this is necessary. Unlike David Shields, I don't emphasize copyright. I tell students that it is important to cite borrowed material in case your reader or listener would like to follow up on some quote, and to read more. Here's a perfect example: #573 above is a quote from Prokofiev, a Twentieth-Century composer who will probably be included in one of my 2019 lectures. I'd love to know the context of this quote so that I can use it (and cite it), but I won't get that from Shields. I'll have to start from scratch to find where, when, and why Prokofiev said or wrote this sentence. All I find in the Appendix is that #573 came from Prokofiev. I'm not even sure if he's referring to Dmitri Prokofiev, the composer, or Fred Prokofiev, the barkeeper.

Aside from my disagreement with David Shields over the provenance of these quotes, I found this to be an intriguing, thought-provoking, and worthwhile book. I marked many of the quotes to re-visit when working on various upcoming projects, and some just to think about further. If you have an interest in writing, reading, truth, or fiction vs. nonfiction, get your hands on this book! (Just know that not all of the entries come from the same mind!)

Reality Hunger is made up of short, numbered entries that circle around a particular cryptically-named topic: Memory, Books for people who find television too slow, Contradiction, Thinking, Manifesto. Don't get too hung-up on the section titles, though, because the numbered entries are all interesting, even if the section titles are not inviting. Check this one out:

615 What actually happened is only raw material; what the writer makes of what happened is all that matters.

This rings true for me, the creative nonfiction writer, because I take an experience, a thought, a place, or even the concert I'm watching on PBS right now, and create some analysis of it. It is a fact that I am watching the Vienna Philharmonic New Year's concert right now on my TV. You can't argue with that. To make this story my own, I have to provide some sort of analysis or reaction. You may disagree with me that this concert is an annual treat, but you can't disagree with me that I see it as an annual treat. Tonight's host, Hugh Bonneville (from Downton Abbey) was just standing in the Vienna Opera House!!! You may not be excited by Hugh Bonneville or the Vienna Opera, but I am because I am a Downton fan and I got to tour the Vienna Opera when I was there in 2015. I remember its opulence, and I remember being impressed at how important opera is to Viennese culture. While you may not agree with me or share my taste or travel history, but reading my thoughts, you understand why I enjoy watching this concert on TV. Maybe I haven't convinced you to watch it, but I have explained my music nerd-ness. Go back to #615 above and read it again.

|

| The Vienna Opera on the Ringstrasse, 2015 |

573 To write only according to the rules laid down by masterpieces signifies that one is not a master but a pupil.

Think about Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms (staying in Austria) for example: if they hadn't broken the musical rules they were taught we probably wouldn't remember them today. They broke the rules and created new art that got attention. They were innovators! I chose this excerpt because it illustrates the concept in this book that got the biggest reaction out of me. At the end of the book is an Appendix. Here, the author, David Shields, explains that the numbered quotes were not all his original thought. Some are. Some, like #573 above, are not. Personally, I did not appreciate not knowing as I read the book that these were not all David Shields's thoughts. In fact, in the Appendix he writes, "However, Random House lawyers determined that it was necessary for me to provide a complete list of citations; the list follows (except of course for any sources I couldn't find or forgot along the way.)" He encourages the reader to tear these pages out and destroy them. WHAT?!?!?!?! I spend my life teaching college students how to cite their sources and why this is necessary. Unlike David Shields, I don't emphasize copyright. I tell students that it is important to cite borrowed material in case your reader or listener would like to follow up on some quote, and to read more. Here's a perfect example: #573 above is a quote from Prokofiev, a Twentieth-Century composer who will probably be included in one of my 2019 lectures. I'd love to know the context of this quote so that I can use it (and cite it), but I won't get that from Shields. I'll have to start from scratch to find where, when, and why Prokofiev said or wrote this sentence. All I find in the Appendix is that #573 came from Prokofiev. I'm not even sure if he's referring to Dmitri Prokofiev, the composer, or Fred Prokofiev, the barkeeper.

Aside from my disagreement with David Shields over the provenance of these quotes, I found this to be an intriguing, thought-provoking, and worthwhile book. I marked many of the quotes to re-visit when working on various upcoming projects, and some just to think about further. If you have an interest in writing, reading, truth, or fiction vs. nonfiction, get your hands on this book! (Just know that not all of the entries come from the same mind!)

Labels:

copyright,

Creative Nonfiction,

fiction,

Nonfiction,

original thought,

Prokofiev,

quoting,

writing

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)